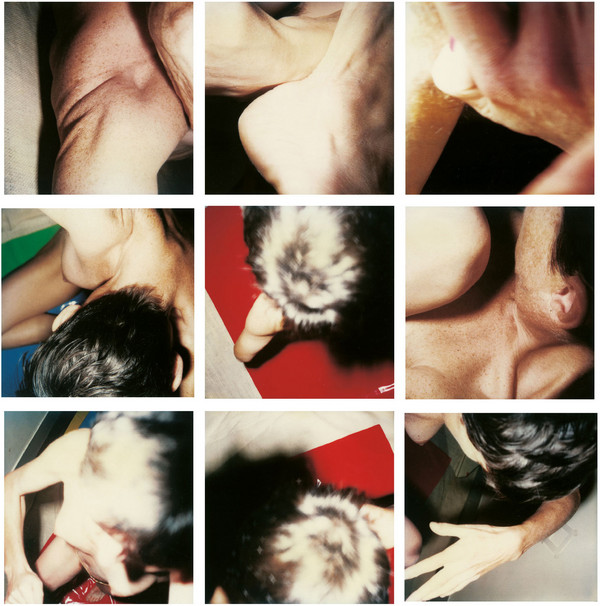

Block XXVI, 1990/92, Nine C-prints of polaroids, mounted on aluminium, 385 x 379 cm, Sammlung Kunstmuseum Sankt Gallen

"Es ist Mittag. Die Nachmittage gehören meiner Arbeit. Die Vorhänge sind geschlossen, durch den Stoff dringt ein gelbliches Licht. Am Boden ist ein weisses Tuch ausgebreitet. Meine Arena. Die Utensilien liegen teilweise bereit. Die Polaroidkamera steht provozierend auf meinem Tisch, neben meinem Skizzenbuch. Ich ziehe über meinen nackten Körper, den Arbeitsmantel. Alles liegt bereit und wartet darauf, in Bewegung gebracht zu werden. Die verschiedenen Spiegelteile, die Stoffe, das Messer, Neocolor, Acrylfarbe, Polaroidfilme; ich friere meistens am Anfang. Ich steige in mich hinein."

Hannah Villiger, Arbeitsbuch, 29.5.1989